Public consultation - there would be a need for it

Two years after the Hungarian government strengthened the institution of public consultation in October 2022, K-Monitor felt the need to analyse in more detail and depth how the practice of public consultation has changed after the reform. We conducted a similar analysis in May 2023.

Photo: Etactics Inc on Unsplash

Although Act CXXXI of 2010 on Public Participation in the Drafting of Legislation has included an obligation to involve the broader society and stakeholders in the drafting of legislation since its inception, the government has simply ignored the rules and in some cases even circumvented them (for example, by submitting significant bills to Parliament as individual motions by Fidesz and KDNP MPs). Instead of public consultation, they tried to gauge citizens' opinions through telephone opinion polls or national consultations with one-off messages.

This practice has been condemned by various EU institutions in country reports since the 2010s, until finally, through the conditionality mechanism, the government committed itself to comply with the rules that have been in place for more than a decade. This commitment is also part of Hungary's recovery plan for 2021-2026. In relation to the public consultation process, the EU mechanism did not yield radically new, effective solutions, structures, or concepts. Instead, it resulted in the delegation of new tasks and powers to the Government Control Office (KEHI), which publishes an annual report summarising ministries' compliance with legal obligations and has the authority to impose fines.

It is questionable whether it is due to the KEHI sanctions (or rather the Commission's scrutiny), but the fact is that since October 2022, when the amendments came into force, the number of draft laws uploaded to the government's website has increased significantly. Between March 2020 and October 2022, only 8(!) proposals were uploaded, and between October 2022 and October 2024, more than 1,700 proposals were uploaded for public consultation by ministries, which is a huge step forward, even if there is still much to be done to improve the effectiveness of public consultation.

The individual proposals are published by each ministry as a "document bundle", in folders, in the "Document Repository" menu of the government's common website, under the "Draft Legislation" section. The "Public Consultation" link on each ministry's subpage also leads to this bulk page. The folders here include

- the text of the draft legislation itself,

- a brief summary of the proposed legislation,

- a justification of the amendment,

- an impact assessment,

- where appropriate, the consolidated text of the legislation,

- and (ideally) the results of the consultations, i.e., a fill-out form in which the ministries summarise from whom and what proposals have been received and what is the government's reaction to them.

Of course, this is not always the case: last year, for example, the Ministry of Defence uploaded the summary of the results of the public consultations as separate documents under the "Other" menu item, which made it essentially impossible to retrace them.

What is the government consulting on?

As of 4, 2024, ministries have uploaded a total of 1,744 document bundles for public consultation, but not all of them are draft legislations. Four ministries have published their GDPR notices in bulk among the draft legislative packages, a practice we described in last year's blog post. This practice is quite problematic, as the privacy notices are essentially only accessible by accident, and some ministries have either not published them at all or have uploaded the relevant documents in bulk under the "Other" section. Furthermore, the government website publishes the names of respondents and their opinions without explicit objections. The draft legislation also contains the government's legislative plans for the first and second halves of 2023 and 2024, but no comments were expected.

Of the remaining 1,736 legislative packages, the government has also published drafts of three strategies (National Active Tourism Strategy, National Cycling Strategy 2030, and National Water Tourism Strategy) and three legislative concepts (Concept of the Hungarian Architecture Act, Concept of the Teachers' Wage Increase, and Concept of Compulsory Medical Screening). The government provided more than 30 days for comments on each of the three strategy papers, and all three received insightful feedback.

However, it's crucial to remember that the government announced at least five other strategies (National Crime Prevention Strategy, National Anti-Corruption Strategy, National Strategy against Anti-Semitism, National Digitalisation Strategy of Hungary, and Hungary Cluster Development Strategy) between 2022 and October of 2024, none of which were subject to public consultation, despite the fact that the law has required this for more than ten years. From K-Monitor's point of view, the lack of public consultation of the anti-corruption strategy is particularly painful. (Similarly, the consultation of the strategy against anti-Semitism, which included quotes from Viktor Orbán, was not consulted; not only was it not consulted with society, but not even with the interested NGOs participating in the Thematic Working Group for Equal Rights; only a short summary was presented at its meeting.)

In any case, it is common for citizens to encounter obstacles when attempting to locate strategies, concepts, or plans that the government or parliament has adopted, or the platforms available for public consultations. For instance, in the "Other" section of the government's website, there are several documents, such as, e.g., the National Energy and Climate Plan of Hungary and the Competitiveness Strategy of Hungary 2024-2030. However, it is unclear which government act has adopted these documents, and their public consultation has not yet taken place.

Regarding the legislative concepts, the Ministry of Interior set a 30-day consultation period for the concept of mandatory medical screening and an eight-day comment period for the other two concepts. However, the number of comments received remained unknown due to the lack of the document summarising the comments.

In addition to the comprehensive legislative concepts and strategy papers on the government's website, K-Monitor found 1,730 draft laws on the website. It is still the case that certain significant draft laws of high public interest are not subject to public consultation. Examples include the twelfth amendment to the Fundamental Law on the Sovereignty Protection Office and digital citizenship, and the thirteenth amendment to the Fundamental Law on the President's power to grant pardons. Fidesz MPs formally tabled the legislation establishing the Sovereignty Protection Office, which theoretically does not fall under the Act on Public Consultation, even though Parliament discussed it alongside the Twelfth Amendment. During the debate, the Minister of Justice, Bence Tuzson, and the former Minister of Justice, Judit Varga, argued for the adoption of the proposals. Without a doubt, the proposals would have received more comments if there had been genuine public consultation.

The proposers avoided real public consultation (and, in some cases, parliamentary debate) for many important legislative amendments by only publishing seemingly irrelevant textual changes (such as changing the word "and" to "further") in the submitted draft for consultation. This was obviously not commented on by stakeholders -- the planned substantive change to the amendment was only presented by the ministry in the Legislative Committee of the Parliament. For instance, in December 2023, the Legislative Committee's amendment prompted the Parliament to adopt rules restricting access to public interest data. Similarly, the government avoids consultation when it submits omnibus laws for public consultation—the draft law on the amendment of certain laws for deregulation in the interests of legal competitiveness, which was submitted for public consultation in September this year, envisages the amendment of 19 laws, while the version submitted to Parliament last week already covers 33 laws (including several cardinal acts and the Freedom of Information Act). It is challenging to understand, for example, why the draft bill sent to Parliament wants to change "in case of" in Article 35(2)(r) of Act CVI of 2007 on State Property to "in the event of." The proposers of the bill seem to plan to keep this information secret until it gets to the final, legislative committee stage. However, in the same two-year period, the Government has submitted 54 different international and intergovernmental conventions for public consultation, although they are of relatively little importance. In last year's blog post, we also mentioned that the Government also submitted more than 20 pieces of legislation to public consultation in which the word 'county' [megye] was replaced by the term used for the county as an administrative district before 1949 ['vármegye', literally 'castle county', however, official English translation remains county].

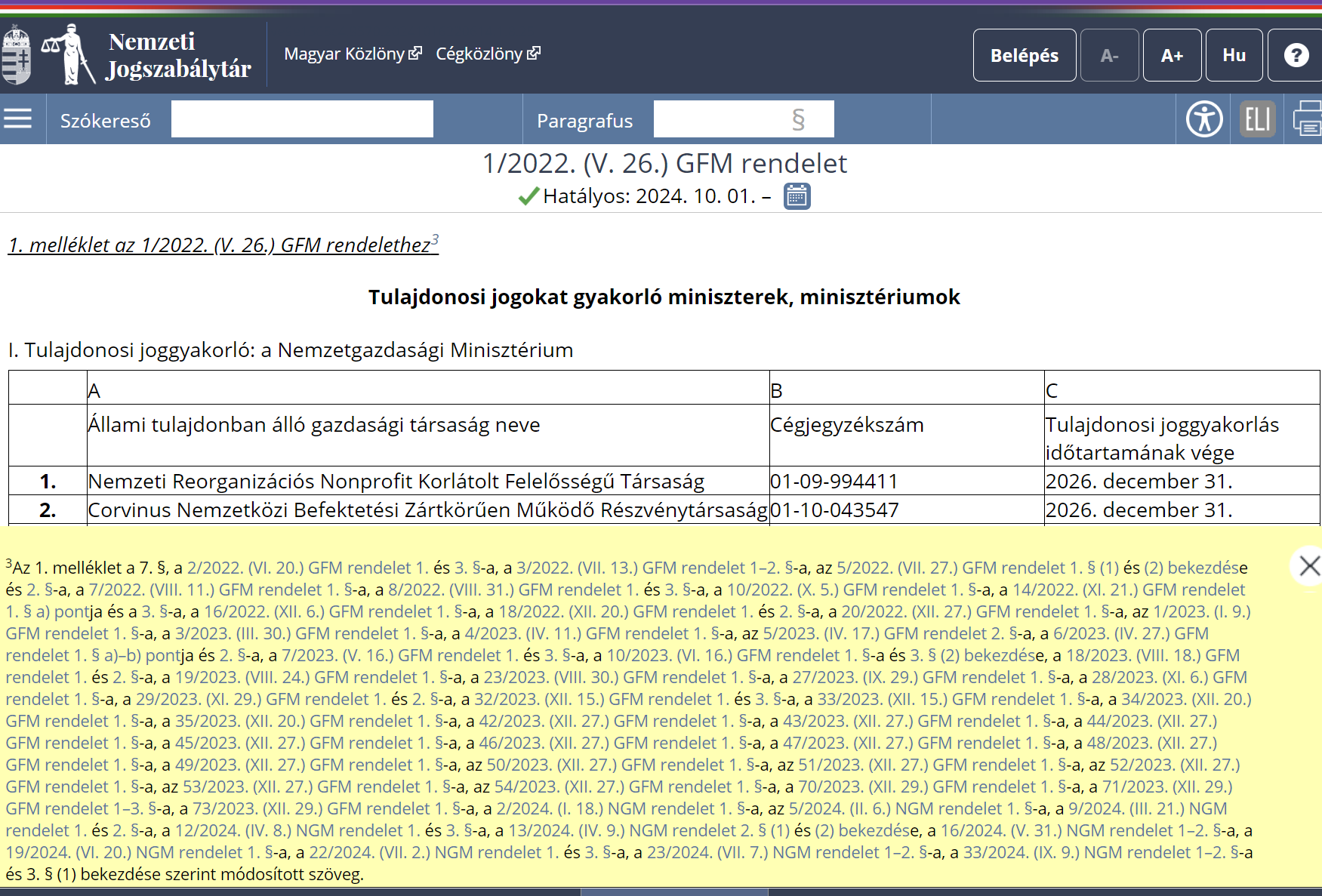

The Ministry of Interior published by far the most proposals (256), followed by the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister with 173 and the Ministry of National Economy with 169. The latter figure could be tempered by the fact that 29 of these were related to Decree 1/2022 (26 May 2002) of the Ministry of Economic Development. This single piece of legislation on appointing the management bodies of state enterprises is a record holder anyway--a total of its 47 different amendments have been submitted for public consultation, of which only two have received a substantive response from citizens and stakeholders. Similarly, Government Decree 141/2018 (27 July 2018), which contains the list of priority (private) investments for job creation, has been subject to public consultation 27 times.

The ministry has solicited feedback on nearly every modification to this table, yet it has only partially captivated the interest of potential stakeholders.

The title of the document bundles still does not help citizens and stakeholders to find the draft legislation that seems relevant to them. It is often meaningless ("Public Consultation") or too broad ("Amendments to certain ministerial or government decrees"), and in about a third of cases only the number of the law to be amended is given—this means that potentially interested citizens have to download virtually every week all the draft legislation submitted for consultation to their computers to find out whether the amendment falls within their competence or area of interest. Citizens' orientation may also be hampered by the fact that often the short summary of the content of the legislation and the explanatory memorandum are meaningless; they are rarely longer than one or two extended sentences. This means that without studying the specific text of the legislation, it is often not even possible to be sure what changes would result from its adoption (not to mention that in many cases the same one or two sentences are uploaded as a "summary of the content" and an "explanatory memorandum").

Consult at Christmas!

According to the legislation on public consultation, ministries must publish drafts in time to allow "sufficient time for the draft to be considered on its merits and for comments to be made," which should be no less than eight days. This requirement has been interpreted rather formally, as only 6 of the 1,730 draft laws examined during the period under review had a longer deadline of more than 8 days set—the longest, 16 days, was bizarrely linked to the judicial reforms, which were not even formally submitted to the Parliament by the Government.

It is also noteworthy that, unlike all other ministries, the Ministry of Construction and Transport includes the day of publication in the eight-day deadline, so that these deadlines are actually only seven days, which may be too short not only for more complex, large-scale draft legislation but also in cases where ministries are putting a large number of drafts out for public consultation at the same time. This has been particularly the case in the run-up to Christmas in the last two years, with ministries launching 161 consultations in December 2022. In December 2023, the number of drafts reached 184. This contrasts quite sharply with January 2023 and 2024, when a total of 28 and 29 drafts, respectively, were in consultation for the whole month. Interestingly, ministries were reluctant to upset citizens with public consultations in May 2024, before the European Parliament and municipal elections, consulting only 28 drafts during the entire month.

Unfortunately, since our last analysis, we have not seen any significant improvement in the technical implementation of the consultation of documents submitted for public consultation. Overall, the current practice essentially consists of individual ministries submitting proposals under the appropriate menu item on the whole-of-government portal—or elsewhere, as evidenced by the Ministry of Defence's practice previously mentioned. This represents a rather high entry threshold for both potential stakeholders and ordinary citizens.

Popular consultations

Of the 1,730 draft laws uploaded for consultation by 4 October 2024, the ministries have uploaded the summary of the public consultations for 1,455 draft laws related to the three strategies. The fact that the deadline for public consultation and publication has not yet expired explains only a minority of the missing summaries. Of the 1,455 published summaries, around two-thirds (963 cases) received no comments at all, whereas 493 cases recorded at least one substantive comment. This does not represent a significant improvement compared to a year and a half ago; as explained above, this is partly due to the content of the drafts (technical legislative amendments) and partly due to the high entry threshold mentioned above.

This is also explained by the fact that by far the most interest has been generated by drafts that have been widely reported in the press or that have successfully mobilised a major social group. One example is the Status Law of Teachers, which received 1696 comments, including 1644 from individuals and more than fifty from professional organisations. Although the Statute Law may not be considered a triumph of public consultation, we can observe instances where consultation yields tangible outcomes for stakeholders. In the summer of 2023, the Ministry of Interior published another bill that attracted press coverage: this would have made it compulsory for general practitioners to book appointments for patients to see specialist doctors. No fewer than 1,895 people (mainly general practitioners, alongside with professional chambers) expressed their disapproval of the proposal, and the Ministry of Interior backed down on the idea virtually before the public consultation had closed.

It is still evident that the professional chambers in the health sector (the Medical Chamber, the Hungarian Chamber of Healthcare Professionals, and the Hungarian Chamber of Pharmacists) are seriously facilitating participation in public consultations, and this is probably also the reason why a large number of sector workers participate in consultations. In last year's analysis, we reported that, in addition to professional organisations, more than 100 individuals, mostly doctors and dentists, have commented on the planned amendments to the various health-related ministerial (244) and governmental (132) decrees announced in December 2022, as well as on the draft ministerial decree on the indicator-based performance evaluation of general practitioners and dentists (115). Health workers have remained very active over the last year and a half: 243 respondents commented on the government decree on the 2024 wage increase and 112 on the government decree on the general wage increase for health workers. A number of health issues also reached the wider society: 122 people objected to mandatory screening tests for eligiblity for work (although one respondent expressed agreement with the proposal).

Perhaps it is worth explaining that, in addition to health, education-related bills also generated debates: the bill on the timeline of the 2023 school year received 167 comments; most of the contributors disagreed with the longer winter and shorter summer holidays compared to previous years, and more than 100 people expressed their opinions on the regulations related to the increase in teachers' salaries and the status law. The government decree on mobile phone use in schools received comments from approximately 80 people, 64 of whom were individual contributors.

More people seem interested in cases where law changes will affect them personally. For example, in our study from last year, we noted that 279 people commented on the draft amendment on the administrative procedure about the battery factories in Debrecen and Iváncsa, even though the Ministry seemed to be trying to hide the consultation. Many people were interested in the amendments of the Family Housing Support Program in December 2023—about 98 people commented on this draft. The "amendment to the Act on the Amendment of Act LVII of 1995 on Water Management," known as "well amnesty" was extensively covered in the news, and garnered 68 comments in May 2023.

The draft "Provisions on the further simplification of the functioning of the state," received 86 responses, and it was not particularly well-received. This omnibus bill also got rid of the automatic deductibility of trade union membership fees, which trade unions and trade unionists did not like very much.

However, 222 drafts (almost 45% of the 493 cases) received only one opinion during the public consultation, a figure that is even more concerning given that Ms. Hajnalka Kertész, who appears to be the most active respondent by all accounts, expressed 77 of these opinions.

Who is giving their opinion?

In total, almost 4200 stakeholders have taken part in a public consultation over the past two years; most of them (at least 3500) are individuals, with a further 400 stakeholders identified as trade unions, interest groups, chambers, or other social organisations. A relatively large number of companies also commented on the drafts. However, it is difficult to calculate accurate, comparable figures because for some drafts the summaries include the results of (direct) consultations with both public authorities (i.e. government and other public bodies) and strategic partners, which in practice means that for institutional actors it is not always possible to distinguish whether the respondents have made their proposals as part of normal public consultations. Several private respondents disclosed their affiliations with organisations, but it wasn't always evident if they made their comments as legal and organisational representatives of the organisation, or as individuals.

The same individual (Hajnalka Kertész), who was already prominent in our analysis a year and a half ago, has provided her opinion on a total of 137 proposals (as previously mentioned, she was the sole respondent in 77 of these), covering a wide variety of topics. In terms of the number of consultations, as already mentioned, the professional chambers of health professionals were quite active, with the Hungarian Chamber of Healthcare Professionals (MESZK) participating in 33 consultations, the Medical Chamber in 27 and the Pharmacists’ Chamber in 20. The Hungarian Catholic Bishops’ Conference and the Reformed Church expressed their opinions in 19 and 9 cases, respectively. In the field of education, the Civil Platform for Public Education and the Trade Union of Teachers (PSZ) also participated in the consultation on more than 10 drafts. MOL (Hungarian Oil and Gas Plc.) was the most active among companies (15 drafts), and the Hungarian Helsinki Committee was the most active among NGOs (12). 85% of the respondents made suggestions on only one piece of legislation; the vast majority of them were private individuals who wanted to have their say on either the Statute Law or the Debrecen and Iváncsa battery factories.

What will the Government do with the proposals received during public consultation?

The summaries published by the ministries also allow us to draw conclusions about the fate of the comments. In these summaries, the ministries put together the most common, substantively related, and technically important comments. They then give a short response explaining the legal or technical reasons why they don't agree with the comments. In practice, these justifications are based on a template, and the Government is not obliged by law to provide more detailed information than this. Again, the definition of a substantive related comment and its grouping vary from ministry to ministry, making it impossible to pinpoint the precise number of diverse opinions and comments received on a proposal. The ministries identified a total of 3112 proposals and comments, the most of them concerening Status Law, the National Cycling Strategy, the amendment to the teachers' pay scale, and the amndment of Real Estate Registry Act. The overall outcome is disheartening: the proposers rejected at least 88% of all opinions due to legal or technical reasons.

In 371 cases, the ministries did not provide information on the reason for rejection: in a small proportion of these, (66 comments in total -- only 2% of all comments), they indicated that the opinion was accepted by the ministry. In 22 cases, the respondents indicated that they supported the legislation, and, as appropriate, in these cases the relevant cells of the template were not filled in.

The reasons for rejection are still not dominated by legal arguments; despite the varied template wording, they still mostly reflect a simple refusal by the Government to take the proposal into account. Of the "technical reasons for rejection," the Government used the arguments "the amendment is not necessary; the regulation is provided for in the current legal environment" in around 1,119 cases and "the draft implements the Government's decision" in a further 1,046 cases. Of course, those whose proposals were rejected on "legal" grounds are no better off. The rejection of 995 comments occurred due to their "contradiction to the legislative intent" and 935 due to their "exceeding the scope of the regulation."

The overall picture suggests that progress in the last two years has been rather formal in the area of public consultation. The tight deadlines indicate that draft legislation is usually published at a relatively late stage, when the government's legislative machinery is already well under way, making it difficult to have a real input to the process and raising questions about whether ministries are really committed to wider involvement. Nonetheless, the increased number of consultations has shown that many interest representations, civil society organisations and citizens are keen to participate—or wish to express their protest in this way.

If the government intended to really involve experts and the public into the legislative process, public consultation could be improved in several ways:

- The current publication system should be reviewed: instead of publishing different bundles of documents, it would be useful to publish on the government website the proposals for consultation according to their thematic. Labelling would also be helpful, especially as the portfolios of some ministries may cover a wide range of topics. It would be useful if ministries could follow a uniform set of rules for publication.

- It would also be important to ensure that both proposals and drafts can be followed up; those involved in consultations may be interested in the final text and content of a proposal and when it is adopted. This is especially true for public consultations involving the amendment of omnibus laws or the inclusion of seemingly technical textual changes in the draft.

- Ministries should consider the legal requirements when setting consultation deadlines, keeping in mind that lengthy laws require more time for comments. Do not apply the eight-day deadline in a mechanical manner.

- It would be useful if the Government were to announce legislative concepts and main directions before the publication of a specific draft law—we can currently learn about upcoming regulations from Facebook-posts. It could be considered that the Government should publish the detailed impact assessment studies as well. It may be recalled that K-Monitor has been suing the Ministry of Interior for almost three years for the secret impact assessment studies on the basis of which the Government is carrying out the health care reform.

- We also recommend avoiding mechanical solutions concerning "the summary of draft legislation" and "the explanatory memorandum"; at the very least, these documents should show the direction, the subject matter and the justification for the legislator's decisions. We shouldn't expect citizens to read tens of pages of legal documents they might not even understand.

- In particular, it would be important to promote public consultation on proposals likely to have a major impact and to attract greater public interest (health, education, job creation, migration, child protection, etc.).

- As soon as possible, the ministries should stop abusing the Legislative Committee's procedure -- the intended text of the proposals should be clear from the beginning. This committee should, in theory, only be concerned with the coherence, the correctness of the language, and the technical details of the legislative texts. Presenting complete packages of amendments at this stage not only misses the final verification stage of the legislative process, but also undermines the credibility of the entire consultation process.

K-Monitor prepared this analysis using data published on kormany.hu until 4 October 2024. We analysed the PDFs summarising the public consultations by machine reading and then verified them. Due to the different publication practices of the ministries, there may be uncertainties about the exact number of respondents (for example, due to the inclusion of organisational affiliations and the use of married names), but these should have minimal impact on the figures we report. The picture we report is incomplete because we only have ministry documents. Over 100 public consultations have not been summarised by ministries in the official format required by law.

0 Hozzászólás:

Legyél te az első hozzászóló!

Hozzászólás írásához be kell jelentkezni: